By Varun Matlani (varun@matlani.in)

The Delhi High Court vide its judgement in Dabur India Limited v. Ashok Kumar & Ors. has silently drafted a new ‘domain law’ for India (slightly unclear on whether this law is restricted to domain names such as .in, .co.in, registrar of which is National Internet Exchange of India (NIXI)).

Facts

This case involved the petition wherein the Plaintiffs, i.e. Dabur India Limited, hold the trademark across various classes for the word “Dabur”, which is also recognized as a well-known mark under the trademark law. A few miscreants registered multiple domain names such as “www.daburdistributor.com” “www.daburfranchisee.in” et al. Fundamentally, using the term “dabur” with some abstract term to misrepresent franchisee/distributorship opportunities, and these individuals were not authorized representatives of Dabur.

When Delhi High Court (“DHC”), tried to trace them, they couldn’t due to vague registration details submitted by these registrants during registration from WHOIS Data. Due to this, the DHC took a step of creating a law for domain names in India through this 200+ page judgement.

[WHOIS is a database wherein you can locate the registrant of a domain name, their address, name, email, registrar, etc. and it is mandatory for Domain Name Registrars (“DNRs”) to submit this data to ICANN and WHOIS. However, there is no possible way to actually ascertain whether details entered by the user are correct or not. Additionally, almost all the DNRs today provide a Privacy Protect feature, i.e. they submit their details to the WHOIS, thereby representing themselves as the owner, whereas someone else is the true Beneficial Owner of a domain name. There is no law / requirement for verification of who owns the domain, and its not a critique, rather a mature understanding of the international community that it is impossible to identify someone, and if not impossible, it is restrictive to make people disclose the data, further, there are multiple remedies available, which shall be discussed later in this essay, which an aggrieved party can seek.]

This case is extremely important and interesting even by seeing the parties to the case, it is essential to understand the functions of each of these:

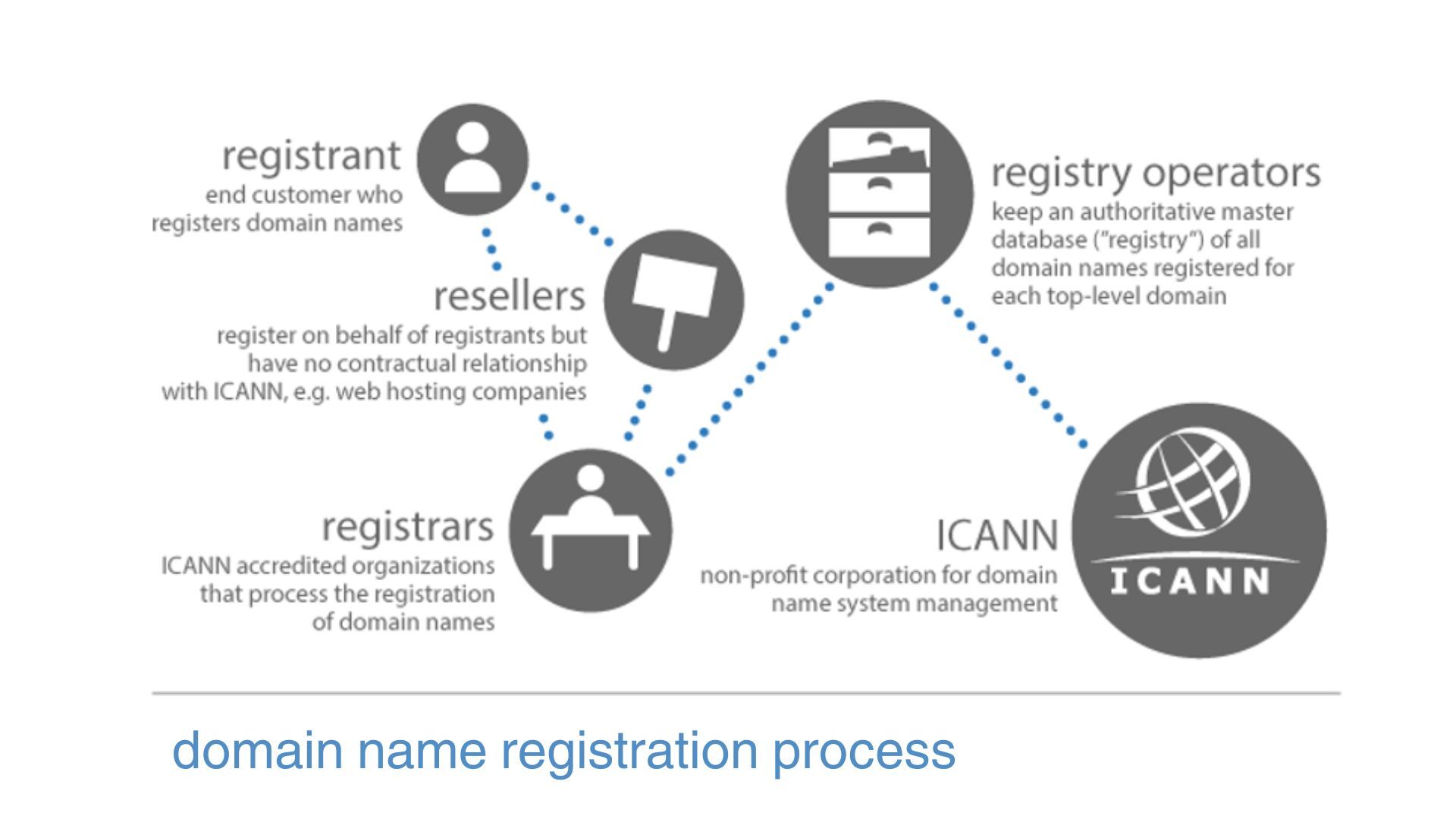

- Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN): Overall coordinator and policy-maker for the global Domain Name System (“DNS”), further, it is responsible for maintaining root DNS. This accredits Domain Name Registrants and Registries. In this case, ICANN (rightly) did not submit to the jurisdiction of the DHC however made submissions to assist the court.

- Domain Name Registrants – these are the ultimate registrants of any domain name. For instance, “.com” is exclusively managed by Verisign, these organizations operate the WHOIS service for their domain name, and they further accredit DNRs. In India, domains such as .in, .co.in, .gov.in, are registered by NIXI (which intends to become a new regulator for domain names in India). Just like a land registry office, does not own the land, yet has all the powers to record and strike off, these companies exclusively have registry powers over the domain, but have to act completely in accordance with ICANN, and are (and should be) toothless, for instance, if you wish to register a completely obscene or illegal sounding domain like “www.buycocaine.com”, there is no provision by which either ICANN or these registrants can stop you, and this is an essential analogy to note to further understand this judgement.

- Domain Name Registrars or DNRs: These are like brokers registered with DNRs which assist in registering a domain name with the registry and assist the registrant with DNS management and other services essential for pointing the domain towards their intended host site, for analogy, an individual can only place the trades on NYSE or NSE through a broker, similiarly, no one can directly register domain with registry such as Verisign or NIXI, and need to go through the DNRs. In the said case, the DNRs were GoDaddy, Hostinger and a few others.

- Registrant – is the domain name owner.

(Image Source: ICANN)

The agreement structuring is such, ICANN has agreement with Registry Operator (Verisign, Nixi etc), Further, each DNR has agreement with ICANN and Registry, and finally the Registrant.

With this background and understanding of each functionary in the process of registering and operating a domain – the next part of this essay analyses the guidelines passed by DHC, and whether DHC has the jurisdiction to operationalize such guidelines.

Jurisdiction of DHC

DHC issued a series of guidelines, if adopted/operationalize will in effect give birth to a new law for domain names. Further, it is unclear whether these directives are for DNRs who register NIXI domains or even for those who register other gTLDs such as .com / .net / .org / .ai

Seemingly, since facts of the case suggest that many of the domain name variants used by miscreants included gTLDs, this is a blanket direction. Which is a subject matter of international jurisdiction, and much beyond imaginable scope of DHC.

Jurisdiction of DHC with respect to gTLDs

As explained above, except for Registrant, all the three entities, for a gTLD perspective operate outside of India, and have no mandate to adhere to jurisdiction of DHC since DHC has no locus.

Further, even if it were to be argued that ‘Registrant’ is an Indian, a Registrant can choose at the time of registration where is his ‘domain’ which is an asset for him should be based of. If an Indian resident/citizen, chooses it to be some offshore place such as Mauritius or Cayman Islands for registration, not only he is not subject to (wrt Domain name) to Indian jurisdiction, but further, is not required to even pay for GST, since now the entire asset is created outside of India, and ownership is conferred digitally, and consideration is paid in a non-Indian currency.

Jurisdiction of DHC w.r.t. NIXI or .in Domains :Why DHC Cannot Have Nationwide Jurisdiction

Before analysing DHC’s jurisdictional claim, it is essential to understand the constitutional scheme governing High Court jurisdiction in India.

Article 226(1) of the Constitution states that every High Court shall have power “throughout the territories in relation to which it exercises jurisdiction” to issue writs. The key phrase is “territories in relation to which it exercises jurisdiction” – for DHC, this is the National Capital Territory of Delhi, not the entire nation.

Article 226(2), inserted by the 15th Amendment in 1963, extends this slightly – a High Court can exercise jurisdiction where the cause of action arises, even if the respondent is outside its territory. However, this provision was intended to provide access to justice for petitioners, not to confer nationwide legislative powers upon a single High Court.

Article 141 reserves nationwide binding effect exclusively for the Supreme Court: “The law declared by the Supreme Court shall be binding on all courts within the territory of India.” No such provision exists for High Courts. A High Court’s decision, even on interpretation of a central law, has only persuasive value outside its territorial jurisdiction – it is not binding on other High Courts, let alone on foreign entities operating globally.

The Supreme Court in Union of India v. Alapan Bandyopadhyay reaffirmed this principle with striking clarity. The Calcutta High Court had set aside an order of the Central Administrative Tribunal’s Principal Bench at New Delhi. The Supreme Court declared the Calcutta HC’s order as “ab initio void” – legally void from inception – because the Calcutta HC had “usurped jurisdiction” by entertaining a matter where the tribunal fell within Delhi HC’s territorial jurisdiction. The Court held that Calcutta HC passed the order “without jurisdiction” and the principle from L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India (1997) was reiterated: judicial review of tribunal decisions can be exercised only by the High Court within whose territorial jurisdiction the tribunal falls.

If a High Court’s order regarding a tribunal sitting in another city is void ab initio, how can a High Court’s directions to foreign corporations operating globally be valid?

The “High Court of India” Problem

There exists a controversial obiter dictum in Kusum Ingots & Alloys Ltd. v. Union of India (2004) where the Supreme Court observed that an order questioning constitutionality of a Parliamentary Act “will have effect throughout the territory of India.” This observation has been relied upon by various High Courts to justify nationwide directions.

However, legal scholars have consistently criticized this obiter as “bad in law” and “not legally sustainable.” The criticism is straightforward: this observation creates a “High Court of India” – a concept not envisioned anywhere in the Constitution. If every High Court can issue orders with pan-India effect, what happens when Delhi HC and Bombay HC issue contradictory directions? Which prevails? The Constitution provides no answer because the Constitution never contemplated such a situation – precisely because High Courts were designed to have territorial jurisdiction only.

The matter is so unsettled that in Union of India v. Sanjiv Chaturvedi (2023), the Supreme Court acknowledged the tension and referred the question to a Larger Bench. The law, therefore, remains unclear – and in this state of uncertainty, DHC has proceeded to issue what are effectively legislative directions to entities across the globe.

How DHC Justified Its Jurisdiction

Despite these constitutional limitations, DHC assumed jurisdiction over foreign DNRs through the following reasoning, primarily drawing from its earlier decision in Neetu Singh v. Telegram (2022):

First, the Court invoked the “effects doctrine” or “long-arm jurisdiction” – since DNRs actively offer services to Indian customers, earn substantial revenue from India, and the infringement/fraud occurs within India affecting Indian victims, Indian courts have jurisdiction. The Court observed that “conventional concepts of territoriality no longer exist” in the cloud computing era.

Which might be true, but the ‘power’ and ‘jurisdiction’ is then restricted to cure the mischief, not to create a law and pass pan-India direction.

Second, the Court relied upon the inherent powers of High Courts, citing Indian Bank v. Satyam Fibres (1996) and Krishan Yadav v. State of Bihar (1994) for the proposition that High Courts are vested with inherent powers to “maintain their dignity, secure obedience to their process and rules and give effective reliefs.”

Third, the Court leveraged a contractual hook – Clause 5.5.2.1.4 of ICANN’s Registrar Accreditation Agreement permits termination of a DNR’s accreditation if it fails to comply with orders of a “competent court.” ICANN’s own position, as recorded by the Court, was that “all DNRs have to comply with local laws” and “orders of competent courts must be implemented.” DHC essentially declared itself a “competent court” and proceeded on that basis.

Fourth, and most critically, the Court wielded Section 69A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 as an enforcement mechanism. The Court held that repeated non-compliance by DNRs can be construed as violation of “public order” – since frauds affect society at large – thereby triggering the power to direct MeitY and DoT to block non-compliant DNRs from offering services in India.

Which is again acceptable for the facts of the case but bad law when considered in light of issuing blanket directions.

Guidelines Issued by DHC –making of a new ‘Domain Name Law’

Direction (i) – Privacy Protect as Opt-In

DNRs shall not resort to masking of registrant details on a default basis. Privacy protection shall be offered only if Registrant specifically chooses it, as a value-added service with additional charges.

Comment: This has no rationale. In any situation, if a owner of domain name intends to do any mischief, even if the privacy feature is not bundled, he would surely use the same. Further, in recent times this feature has become free of cost, and a large number of domain names are privacy protected. Further, it is essential to note, that this is not a feature provided to bypass laws, rather an ‘essential’ feature necessarily to be provided under ICANN-DNR agreement.

Direction (ii) – Mandatory Disclosure Within 72 Hours

Upon request from entities with legitimate interest, LEAs, or Courts, the following data shall be disclosed within 72 hours: Name of Registrant, Administrative and Technical contacts, Addresses, Mobile numbers, Email addresses, Payment information (credit card, UPI, bank account details), Details of value-added services.

Comment: This would work only when the Registrant is an Indian who has registered a domain name managed by NIXI.

Direction (iii) – Permanent Blocking

If any particular domain name is restrained by an order of injunction or has been found to be used for illegitimate and unlawful purposes, the said domain name shall remain permanently blocked and shall not be put in a common pool in order to disable re-registration of the same very domain name by other DNRs. The appropriate steps in this regard shall be taken by the concerned Registry Operator to ensure that all DNRs having an agreement uniformly give effect to the said direction.

Comment: This directive could only be made applicable to NIXI, since other registrars such as Verisign are not liable to adhere to this. This can be understood with an illustration. Mr. X buys a domain Domain 1 – “www.buyweed.com” or Domain 2- “www.buyweed.in” – now:

Case A: This is just a marketing tactic, and he does nothing illegal. Nothing follows.

Case B: Mr X is found to do something illegal/unlawful. An Indian Court passes an order to block it under Section 69A of IT Act, now this domain name is not accessible in India. However, under the aforesaid Direction 3, DHC wants that this domain should never be allowed to be registered. For instance in this case GoDaddy registers it, the said domain expires, and now available in common pool, where Mr. Y buys it from Hostinger, DHC wants that such domains should never go back in common pool.

However, let us take the case of Marijuana – it is a Narcotic substance banned under NDPS Act, however, legal in Canada, Thailand, perhaps USA. So, wherein the courts have all the power to block the website, they cannot block the domain, since it is very essential to note, that .in domain names are not a property of “NIXI”, anyone across the globe can buy it and mandatorily so, NIXI cannot even place a restriction allowing only Indians to buy it, any domain available is a domain for public use (except domains acquired for restricted purposes such as .bank.in, .gov. or .sbi, .google).

Direction (iv) – No Alternative Domains for Well-Known Marks

For well-known, invented, arbitrary, or fanciful marks, DNRs shall not offer alternative domain names containing such marks.

Comments: Unlawful, Unconstituional, Technologically Impossible.

DHC intends to not allow any domain name which is a Well Known Mark. Now there are few well known marks in India. However, under the international trademark law, well known marks have ‘no’ recognition outside of India. For instance, if XYZ is a well-known mark (WKM) in India, that has no bearing anywhere outside of India. So according to DHC, if www.xyz.com is unavailable, DNRs should not even offer or make it available to register www.xyz.net

But the said WKM, is not even a registered trade mark say for instance in Cyprus or Mauritius, and an entity based out of these intends to use it. DHC has no jurisidciton or no rationale to propose this since WKM is an Indian concept, and they may surely block such domains in India, however, making them unavailable to buy itself is not only impossible from global perspective, but an overreach of law.

Further with respect to ‘variations’ let me take a lighter example – should I be able to register these names if they were available: (1) www.gotomars.com, (2) www.iamintelligent.com, (3) www.holidayinchennai.com,

Technically yes, however, all of them have a component of WKMs, viz. (1) Mars, (2) Intel and (3) Holiday Inn

Direction (v) – No Promotion of Alternatives

DNRs shall not promote or suggest alternative domain names of injuncted domains. Violation would disentitle safe harbour protection.

Comment: When you try registering a domain which is unavailable, you get alternative suggestions, or even a list of which TLDs may be available. For instance, if varun.com is not available, I may get alternative to buy varun.in;

This has no rationale. And violative of 19(1)(g) of the DNRs.

Direction (vi) – Joint Registrar Procedure

For descriptive/generic marks, extension of injunction to other domains shall be through Joint Registrar upon filing of application under Order I Rule 10 CPC.

Comment: Complicated procedure

Direction (vii) – Transfer to Trademark Owner

Infringing domain names shall be transferred to trademark owner upon payment of usual charges.

Comment: So basically if you were able to buy www.gotomars.com; for the fee you paid, you would need to sell this back to Mars. Sounds absurd, beyond jurisdiction.

Direction (viii) – No Promotion Services

Search engines and DNRs shall not provide promotion, marketing, or SEO services to infringing domain names.

Comment: Partially acceptable

Direction (ix) – Grievance Officers

All DNRs offering services in India shall appoint Grievance Officers within one month, failing which they shall be treated as non-compliant

Comment: Acceptable

Direction (x) – Email Service Sufficient

Service by email to Grievance Officer shall be sufficient service for Court orders. DNRs insisting on MLAT shall be treated as non-compliant.

Comment: Partially acceptable

Direction (xi) – Section 69A Blocking

In appropriate cases of repeated non-compliance affecting society at large, Court may direct blocking under Section 69A IT Act.

Comment: Partially acceptable

Direction (xii) – TMCH Implementation

All Registry Operators with ICANN agreements shall implement Trademark Clearinghouse services.

Direction (xiii) – e-KYC Verification

All DNRs offering services in India shall undertake verification per CERT-In Circular dated 28th April, 2022.

Comment: Beyond jurisdiction of DHC to create a law for India. Further, such KYC requirement is not mandatory for any other domain name registrant, and I doubt it can be made mandatory even for NIXI domain names.

Direction (xiv) – Data Sharing with NIXI

All DNRs enabling .in domain registration shall provide registration data to NIXI within one month and update monthly.

Comment: Creation of a surveillance state. Beyond jurisdiction of DHC.

Practical Suggestions

- India should become part of – Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) is an offering of WIPO, of which India is not a party to. The UDRP is a legal framework for resolving disputes between domain name registrants and third party trademark owners over abusive registration and use of Internet domain names in gTLDs (e.g., .COM, .NET) and ccTLDs that have adopted the UDRP. Created by WIPO and adopted by ICANN in 1999, the UDRP requires all accredited registrars to abide by its terms for domains under their jurisdiction. Any person registering a domain name in these domains must consent to the UDRP. ICANN adopted the UDRP Rules in October 1999, which outline the procedure, and WIPO the leading global service provider.

- Further on, its pointless and unsafe to register domain names from Indian jurisdiction. If a payment is made through crypto and registered in offshore jurisdiction, the only tool left would be of Section 69A – which is rightly so used in cases of actual mischief as in this case.